By Chris Faubel, M.D. – Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are amongst the most widely used pain relievers used in the United States: 70+ million prescriptions are written each year, and if you include over-the-counter NSAIDs, 30+ billion doses are consumed annually. [1] As pain specialist, we should be aware of how NSAIDs work, what adverse effects they can cause, and how to minimize ……………. I will refer to those NSAIDs that preferentially inhibit COX-1 (but also inhibit COX-2) as “nonspecific” or “nonselective”. Those that mostly inhibit COX-2, will be referred to as “COX-2 inhibitors” or “coxibs”. Mechanism of Action of NSAIDs

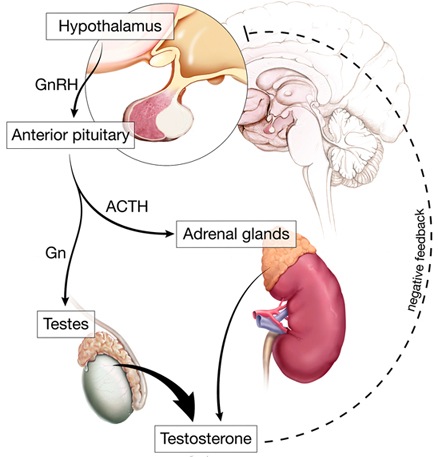

Baseline levels of prostaglandins are created for normal physiologic function. The cyclooxygenase-1 enzyme (COX-1), converts arachidonic acid to prostaglandins (gastric mucosa protective by decreasing acid production), prostacyclins (inhibit platelet aggregation), and thromboxane A2 (aids in platelet aggregation).

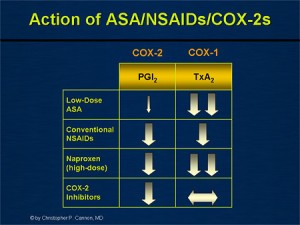

- Low-dose aspirin inhibits the ability of COX-1 to make thromboxane, without having much inhibitory effect on the production of prostacyclins. This collectively inhibits platelet aggregation, and is the reason why long-term use of low-dose aspirin aids in decreasing the incidence of heart attacks.

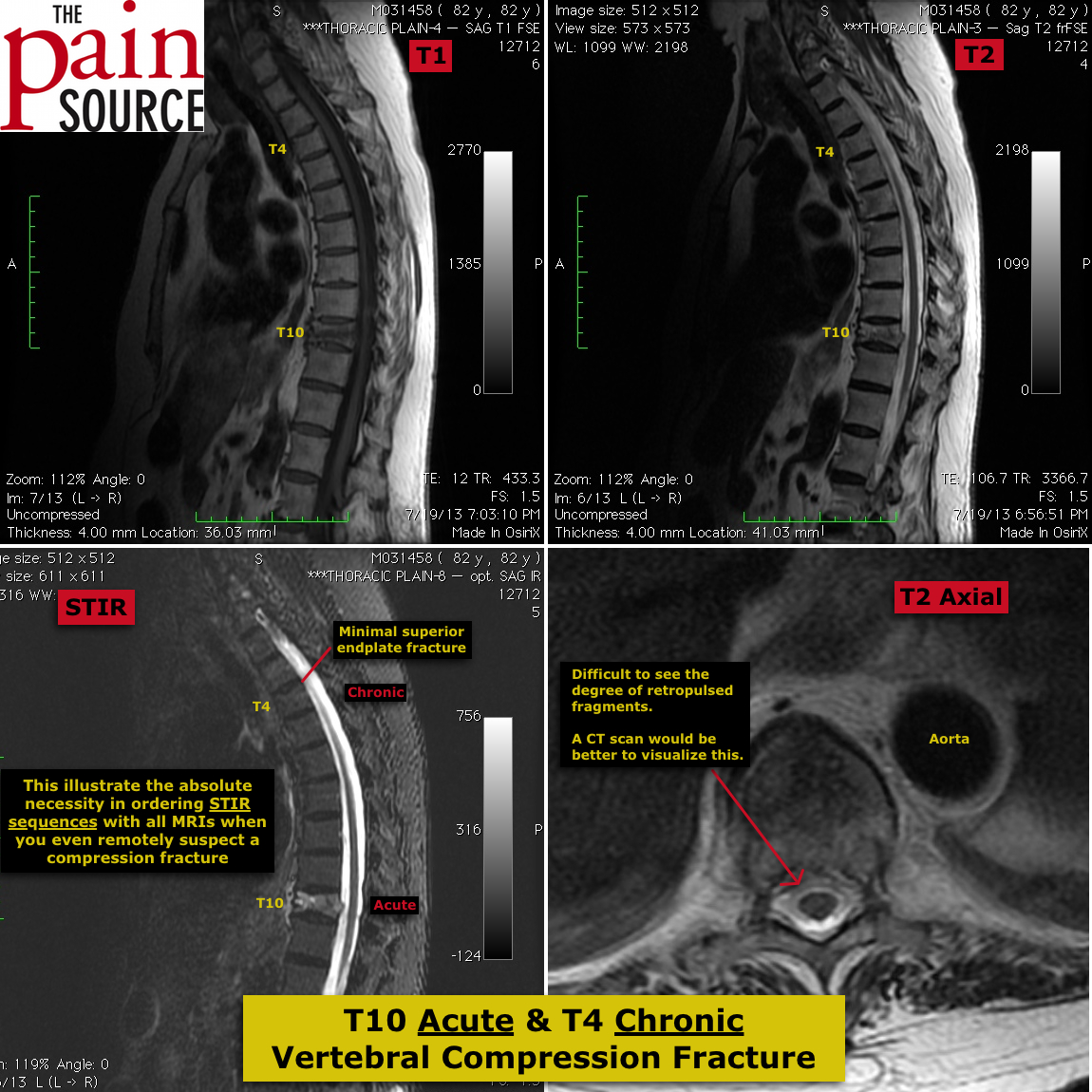

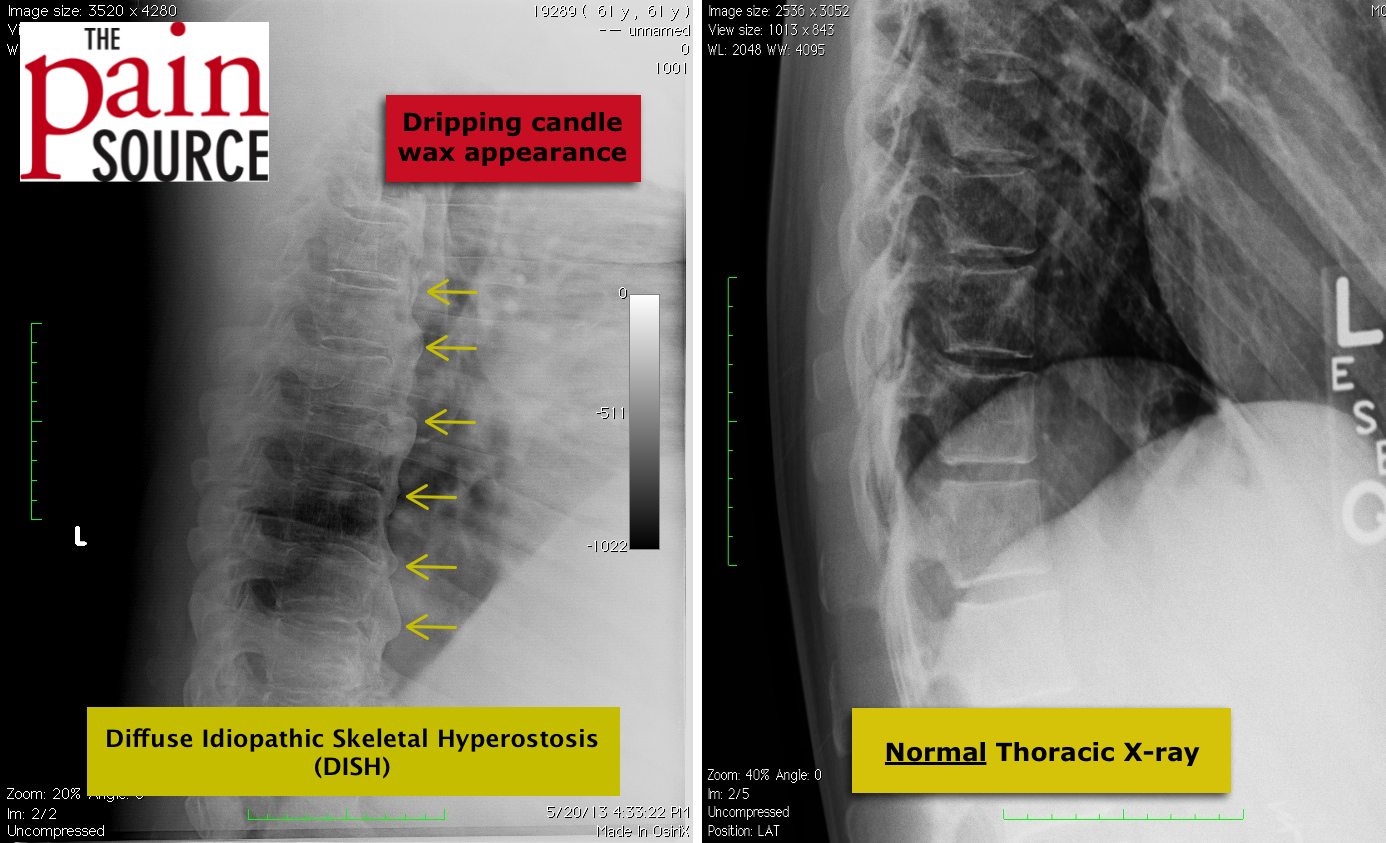

In this same cascade (seen in the pic to the right) is COX-2. While COX-1 is always working, COX-2 is essentially only induced to work when there is inflammation (pain). All NSAIDs block COX-1 and COX-2 to varying degrees.

- Certain NSAIDs preferentially block COX-1, while others were designed to mostly block COX-2.

- Predominantly COX-1 inhibitors: ibuprofen, naproxen, aspirin, ketorolac (Toradol), indomethacin

- Predominantly COX-2 inhibitors: etodolac (Lodine), diclofenac (Voltaren), celecoxib (Celebrex), meloxicam (Mobic), valdecoxib (Bextra – discontinued), rofecoxib (Vioxx – discontinued)

- Gastrointestinal

- Cardiovascular (MI and stroke)

- Renal

- This is if you took asymptomatic patients off the street and performed an endoscopic exam; so they aren’t necessarily symptomatic.

- These are the patients that would seek medical attention. A relatively small percentage of patients, but still a very large number considering the tens of millions of patients taking NSAIDs chronically.

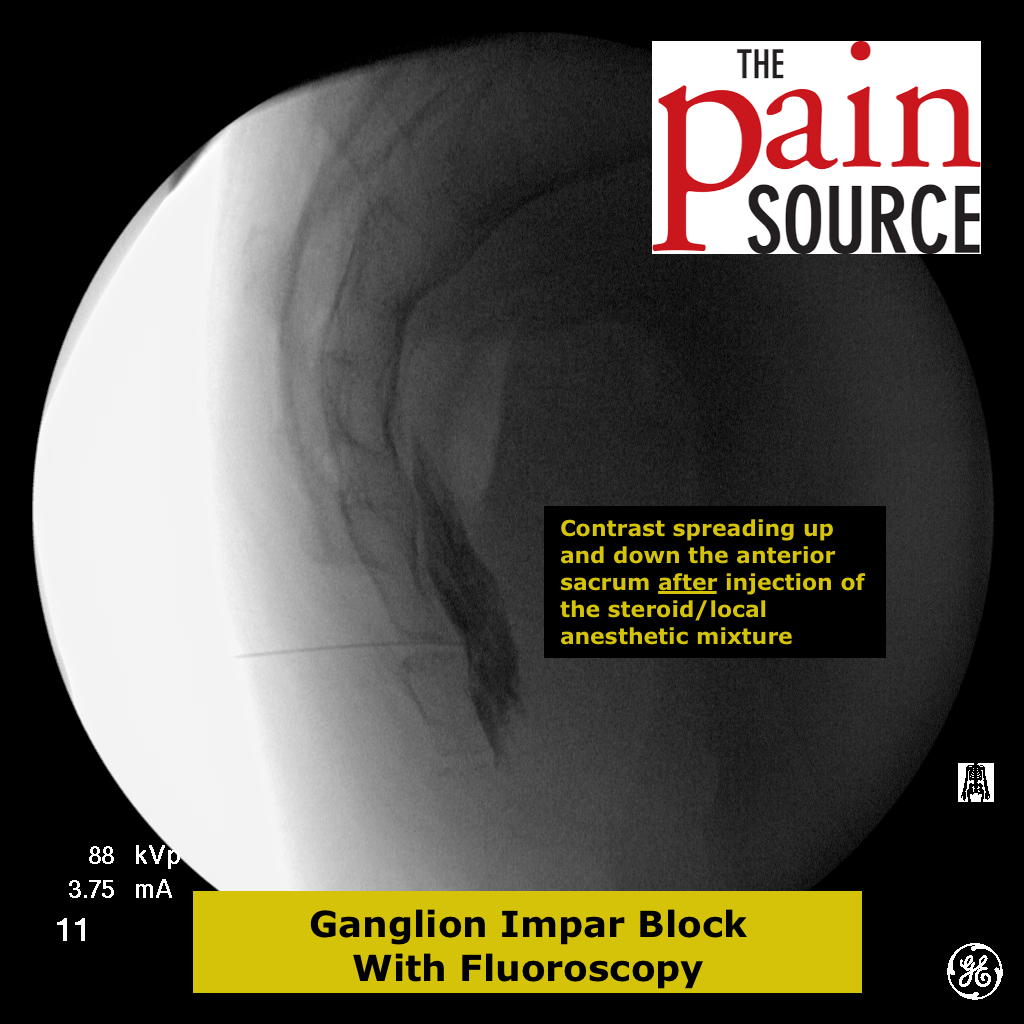

- Note the above image that depicts ketorolac (Toradol) as being the most COX-1 specific. It is of no coincidence that ketorolac is not advised to be used for more than 5 consecutive days, because of the high GI bleed risk.

- Prior upper GI events

- Older age (>65)

- Concurrent anticoagulation use (warfarin)

- Corticosteroid use

- High-dose or multiple NSAIDs (NSAID + low dose aspirin)

- High risk patients should take COX-2 selective NSAIDs + PPI (or not get NSAIDs at all)

- Low-dose aspirin taken concurrently with a COX-2 inhibitor nearly negates the GI-protective effects of the COX-2 inhibitor.

- As many of our older patients are taking low-dose aspirin for the cardiovascular benefits, this is important to know.

- Some physicians use the strategy of combining a proton-pump inhibitor with a nonselective NSAID (for example: omeprazole with diclofenac)

- This has NOT been shown to decrease the number of patients developing dyspepsia.

- PPIs, misoprostol, COX-2 selective – keep in mind, these do NOT eliminate GI risks

- Most bleeds have no antecedent symptoms

- Also keep in mind that the presence of dyspepsia in a patient does NOT mean they will develop serious GI adverse effects

Striking a balance between prostacyclin production and thromboxane production

- As noted above, prostacyclins help to prevent platelet aggregation (cardioprotective), while thromboxane A2 causes platelets to clump (and thus cause cardio issues). Since both of these are produced via COX-1, the balance between prostacyclin and thromboxane presence is key.

- It is important to note that not all NSAIDs that block COX-1, will affect prostacyclin and thromboxane production the same. See the image to the right.

- Note that a pure COX-2 inhibitor will have no effect on thromboxane production, and therefore no effect on inhibiting platelet aggregation like aspirin does. Because of this, it is safe to use COX-2 inhibitors after surgery because it won’t have a bleeding risk.

- High dose naproxen (500mg BID) significantly inhibits thromboxane production all day, while ibuprofen 800mg would inhibit platelet aggregation for 2-4 hours after each dose.

- The cardioprotective, inhibition of platelet aggregation effects of low-dose aspirin are well known.

- But when ibuprofen or naproxen are given before the ASA, they preferentially block the COX-1 and don’t allow ASA to exert its effects.

- In contrast, COX-2 selectives (specifically Vioxx) and diclofenac did NOT interfere with the binding and protective effects of ASA.

- High-dose naproxen (500mg BID) has a strong anti-platelet effect and has NOT been shown to increase the risk of CV events more than placebo.

- Interestingly, low-dose naproxen (220mg BID) DID show an increased risk of CV events over placebo.

Bottomline: All NSAIDs (except high-dose naproxen) have shown an increased risk of cardiovascular events compared to placebo

- This isn’t clearly understood, but it is thought that inhibiting COX-2 (either with nonselective NSAIDs or with COX-2 selectives) causes an imbalance in prostaglandins that leads to sodium retention, decrease glomerular filtration rate (GFR), and increased blood pressure.

- Interestingly, high-dose naproxen has been shown to decrease the GFR and raise systolic BP just as much as COX-2 inhibitors.

References: 1) Wiegand, Timothy. Toxicity, Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Agents. Medscape. Updated: May 20, 2010